In order to better understand patellar instability and why the kneecap (patella) dislocates, it is important to understand the anatomy and function of the knee and patella.

Anatomy

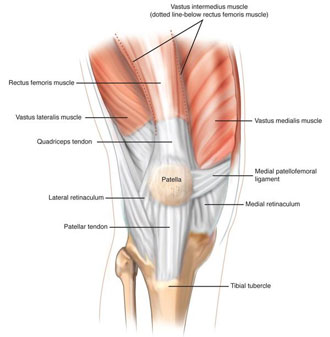

The kneecap (patella) is a small bone in the front of the knee. It glides up and down the groove in the thigh bone (femur) as the knee bends and straightens. The patella has a smooth coating (articular cartilage) on its underside which allows it to slide easily in this groove. The groove in the femur is called the femoral groove, and the femur is also coated with articular cartilage. The patellar tendon is a thick, ropelike structure that connects the bottom of the patella to the top of the shin bone (tibia). The powerful muscles on the front of the thigh called the quadriceps muscles straighten the knee by pulling at the patellar tendon via the patella. There are also smaller rope-like structures (ligaments) on the inner (also known as medial) and outer (also known as lateral) sides of the patella. These small ligaments work with the quadriceps muscles to help keep the patella from coming out of the femoral groove.

The kneecap (patella) is a small bone in the front of the knee. It glides up and down the groove in the thigh bone (femur) as the knee bends and straightens. The patella has a smooth coating (articular cartilage) on its underside which allows it to slide easily in this groove. The groove in the femur is called the femoral groove, and the femur is also coated with articular cartilage. The patellar tendon is a thick, ropelike structure that connects the bottom of the patella to the top of the shin bone (tibia). The powerful muscles on the front of the thigh called the quadriceps muscles straighten the knee by pulling at the patellar tendon via the patella. There are also smaller rope-like structures (ligaments) on the inner (also known as medial) and outer (also known as lateral) sides of the patella. These small ligaments work with the quadriceps muscles to help keep the patella from coming out of the femoral groove.

When the patella comes completely out of the femoral groove, it is called a patellar dislocation. Occasionally the patella will only partly come out of the groove. This is called a patellar subluxation. Patellar subluxations can be thought of as a “mild dislocation”. Most of the time the patella dislocates or subluxes outwardly (laterally). The medial patellar ligament and the vastus medialis muscle are important structures in preventing the patella from dislocating or subluxing laterally. When the patella dislocates or subluxes laterally, their structures are usually damaged. As a result of one or more patellar dislocations or subluxations, the knee can feel unstable. This type of problem is called patellar instability. This feeling of instability occurs because the muscles and ligaments are unable to keep the patella in the femoral groove.

The Patient

Initially, people who dislocate their patella complain of sudden pain in their knee after a plant and twist type of injury or after a contact injury. Sometimes straightening the knee will help the patella go back in the femoral groove. Sometimes the patella stays out of the groove and has to be put back in by a specialist. Regardless, the knee usually swells and sometimes feels unstable. With lateral patellar dislocations a tear in the medial patellar ligament or the vastus medialis muscle may be felt. The patella may also be slightly displaced to the outside (laterally) or feel like it is going to dislocate again if pushed laterally. Finally, it may be difficult to bend and straighten the knee without pain.

Examination techniques that detect excessive movement of the patella in the femoral groove are helpful in determining if there has been a patellar dislocation or if there is ongoing patellar instability. X-rays are often done at the time of the injury to make sure that the bones of the knee are not broken or chipped. Other tests such as Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) are occasionally used to rule out damage inside the knee.

Treatment

The treatment of patellar dislocations and patellar instability depends on the severity of the injury and other associated injuries, and each treatment plan should be individualized. Initially, protection (by use of crutches and a rehabilitation brace), rest, ice, compression, and elevation (PRICE) of the injured knee will help reduce pain and/or swelling.

After a patellar dislocation or subluxation the long-term goal is to return the individual back to his or her previous level of activity. Achieving this goal will depend on the function and stability of the knee. A general knee rehabilitation program which includes strengthening exercises, flexibility exercises, sport-specific muscle re-education, and proprioceptive (biofeedback) retraining is the most important factor in improving knee function and stability. Stability may be improved by a patellar-stabilizing brace. Fortunately, many patients with patellar instability can be managed successfully without surgery. However, even with the most ideal treatment the knee may never be as “normal” as the uninjured knee and modification of activity may be required. Furthermore, some research has identified that individuals who have repetitive patellar dislocations are at greater risk for premature “wear and tear” arthritis (osteoarthritis) of the knee joint. If patellar instability continues to affect a patient despite nonoperative regimens, your doctor may discuss surgical treatment.

The surgical treatment of lateral patellar instability focuses on reconstruction of the medial patellofemoral ligament. This ligament is the most important structure that stabilizes the patella and prevents it from sliding laterally out of the femoral groove. The ligament is reconstructed using a soft tissue graft in an outpatient procedure. The surgery involves small incisions on the side of the knee and takes approximately 2 hours to complete. A nerve block may be used to reduce the postoperative pain, but most patients do quite well and their pain is controlled with ice therapy and oral medications.

The surgical dressings are usually removed on the second day after surgery, and it is fine to shower and get the incision wet thereafter as long as there is no active drainage from the incision. You may not submerge the knee under water for 2 weeks. Keep the steri-strips on the incisions until your first followup appointment.

Recovery

During the initial postoperative period your knee may be kept in a brace for 2-4 weeks until the quadriceps strength returns to normal to protect against a fall or reinjury. During the first two weeks the patient should routinely do ankle pumps, knee slides, and quadriceps isometrics 3-4 times per hour while awake to maintain range of motion and prevent atrophy. Crutches are usually necessary for 2-4 weeks with partial weightbearing for the first 2 weeks and then progressing off of the crutches as tolerated. The knee immobilizer is usually discontinued by 4 weeks after surgery.

Formal Physical Therapy

Therapy will begin after the first postoperative appointment at approximately 2 weeks and usually lasts for up to 3 months after surgery. While the strength and function are restored to normal, a return to aggressive sporting activities is allowed. This usually requires 4-6 months. A patellar-stabilizing brace may be used to add additional support to the knee.

In conclusion, patellar instability is a common problem due to the anatomy of the knee. Fortunately, most patients do well with non-operative treatment and physical therapy. However, if recurrent patellar instability becomes a problem, surgical treatment has been shown to provide excellent long-term stability and a return to previous sporting activities.